|

This is part of a series where I write about my stay in Rwanda and Uganda and what I learned that might be helpful from an EA perspective.

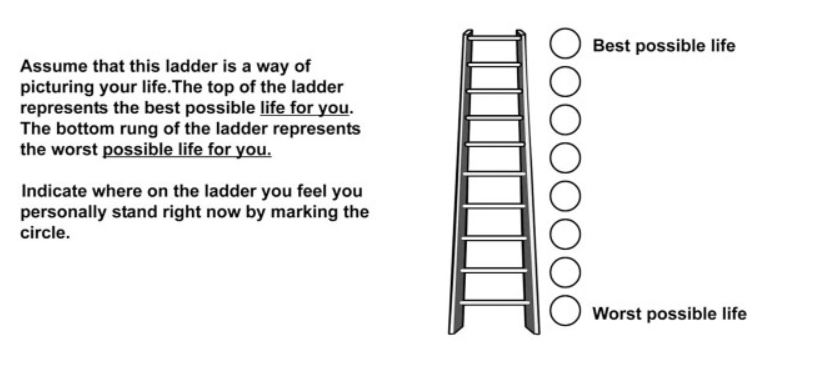

You can see the full list of articles here, which I will add to as they come out. I think the biggest takeaway I had from my experience is that I am even more skeptical of survey methodologies than I was before, and I started off pretty intensely skeptical. The reasons for this is that I think that misunderstandings caused by translation, education levels, and just normal human-to-human communication errors are not only common, but the rule. I explain some things that I think might help mitigate these problems below. First I will list some examples that led to this conclusion. Not understanding hypotheticals. One of my main sets of questions was asking people which interventions they’d prefer. At first I started by asking people just what they’d like charities to do to help, but that was too broad. Around 90% of people could not think of anything. This makes sense if you think about it. Imagine somebody came up to you and asked you what charities could best do to help you. It’s not something that people have thought about much. After that I switched to asking people about paired options. At the end of this, once their minds were more primed to thinking about options, I’d ask the open ended question. The paired questions went along the lines of, “A charity could either pay for one person to go to university, or ten people to go to primary school. What do you want the charity to choose?”. Getting people to understand the question was very difficult, often requiring over three minutes to explain, and even then, it was unclear whether it had really been grasped. They would say things like, “They should do both” or “My children already went to primary school, so I’d ask for university.” Not understanding in general. People did not understand the question (yet answered what they thought it meant anyways) so frequently I had to create a shorthand marking for “didn’t understand”. I would guess that this happened in 20-80% of questions depending on the person. People giving inconsistent answers. An extremely common problem was that people would give inconsistent answers over the course of the conversation. I’d ask them about their job before this one and they would say that they had never had a job beforehand. Later they would refer to working at another farm or as a seamstress. Since I was there I was able to go back and ask them to clarify the previous statement. However, often even then it was unclear whether I’d gotten the correct answer the third time round. It is also my experience that standard surveying techniques do not give surveyors the leeway or incentives to correct inconsistencies or spend a lot of time explaining the question since that would lead to less standardization. I’m not sure the benefits of standardization outweigh the cons of not being able to correct for obvious errors. Refusing to rate happiness. I was asking a 75 year old, illiterate woman how happy she was. First off, she said she was very happy. I asked her to rate it on a Cantril ladder, which is what is commonly used (e.g. by the Gallup Poll) in low literacy settings. It shows a ladder from 1 to 10, with a number on each rung of the ladder, showing worst to best possible life. I also drew a smiley face at the top and a sad face at the bottom, which is also common in these settings. She did not understand the question at all and refused to answer.

Potential solutions

Of note, these issues are actually quite likely to be true in the developed world too, just (potentially) to a lesser degree. Additionally, this is less true for more objective metrics, like whether they have a dirt floor or how many cows they own. Lastly, surveys can be extremely flawed, but this is true for virtually every method available to us. The question isn't whether it's perfectly accurate, but whether it's better than our alternatives, and the case of surveys, so far it's the best we have. To modify Churchill's quote, science is the worst form of epistemology except for all those other forms that have been tried. If you don’t want to miss the next installments and want to stay up to date with my research in general, you can subscribe to my newsletter here, follow me on Twitter, Facebook, or my YouTube channel, where I summarize what I’m reading and convert quality written content into video and audio format.

1 Comment

Delen

9/8/2020 10:40:56 am

Great points and great article! Survey design and analysis is super important and not discussed enough (especially by the media).

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Popular postsThe Parable of the Boy Who Cried 5% Chance of Wolf

The most important lesson I learned after ten years in EA Why fun writing can save lives Full List Kat WoodsI'm an effective altruist who co-founded Nonlinear, Charity Entrepreneurship, and Charity Science Health Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed