A “surgical pause” won’t work because politics doesn’t work that way and we don’t know when to pause4/25/2024 A “surgical pause” won’t work because:

1) Politics doesn’t work that way 2) We don’t know when to pause 1) Politics doesn't work that way For the politics argument, I think people are acting as if we could just go up to Sam or Dario and say “it’s too dangerous now. Please press pause”. Then the CEO would just tell the organization to pause and it would magically work. That’s not what would happen. There will be a ton of disagreement about when it’s too dangerous. You might not be able to convince them. You might not even be able to talk to them! Most people, including the people in the actual orgs, can’t just meet with the CEO. Then, even if the CEO did tell the org to pause, there might be rebellion in the ranks. They might pull a Sam Altman and threaten to move to a different company that isn’t pausing. And if just one company pauses, citing dangerous capabilities, you can bet that at least one AI company will defect (my money’s on Meta at the moment) and rush to build it themselves. The only way for a pause to avoid the tragedy of the commons is to have an external party who can make us not fall into a defecting mess. This is usually achieved via the government, and the government takes a long time. Even in the best case scenarios it would take many months to achieve, and most likely, years. Therefore, we need to be working on this years before we think the pause is likely to happen. 2. We don’t know when the right time to pause is We don’t know when AI will become dangerous. There’s some possibility of a fast take-off. There’s some possibility of threshold effects, where one day it’s fine, and the other day, it’s not. There’s some possibility that we don’t see how it’s becoming dangerous until it’s too late. We just don’t know when AI goes from being disruptive technology to potentially world-ending. It might be able to destroy humanity before it can be superhuman at any one of our arbitrarily chosen intelligence tests. It’s just a really complicated problem, and if you put together 100 AI devs and asked them when would be a good point to pause development, you’d get 100 different answers. Well, you’d actually get 80 different answers and 20 saying “nEvEr! 100% oF tEchNoLoGy is gOod!!!” and other such unfortunate foolishness. But we’ll ignore the vocal minority and get to the point of knowing that there is no time where it will be clear that “AI is safe now, and dangerous after this point” We are risking the lives of every sentient being in the known universe under conditions of deep uncertainty and we have very little control over our movements. The response to that isn’t to rush ahead and then pause when we know it’s dangerous. We can’t pause with that level of precision. We won’t know when we’ll need to pause because there will be no stop signs. There will just be warning signs. Many of which we’ve already flown by. Like AIs scoring better than the median human on most tests of skills, including IQ. Like AIs being generally intelligent across a broad swathe of skills. We just need to stop as soon as we can, then we can figure out how to proceed actually safely.

0 Comments

I’ve been living nomadically for 3 years, & I’m often asked what my advice is for people trying it. Here’s the 80/20 of all my advice:

Other articles you might like: Epistemic status: a parable making a moderately strong claim about statistics

Once upon a time, there was a boy who cried "there's a 𝟱% chance there's a wolf!" The villagers came running, saw no wolf, and said "He said there was a wolf and there was not. Thus his probabilities are wrong and he's an alarmist." On the second day, the boy heard some rustling in the bushes and cried "there's a 10% chance there's a wolf!" Some villagers ran out and some did not. There was no wolf. The wolf-skeptics who stayed in bed felt smug. "That boy is always saying there is a wolf, but there isn't." "I didn't say there was a wolf!" cried the boy. "I was estimating the probability at low, but high enough. A false alarm is much less costly than a missed detection when it comes to dying! The expected value is good!" The villagers didn't understand the boy and ignored him. On the third day, the boy heard some sounds he couldn't identify but seemed wolf-y. "There's a 15% chance there's a wolf!" he cried. No villagers came. It was a wolf. They were all eaten. Because the villagers did not think probabilistically. The moral of the story is that we should expect to have a large number of false alarms before a catastrophe hits and that is not strong evidence against impending but improbable catastrophe. Each time somebody put a low but high enough probability on a pandemic being about to start, they weren't wrong when it didn't pan out. H1N1 and SARS and so forth didn't become global pandemics. But they could have. They had a low probability, but high enough to raise alarms. The problem is that people then thought to themselves "Look! People freaked out about those last ones and it was fine, so people are terrible at predictions and alarmist and we shouldn't worry about pandemics" And then COVID-19 happened. This will happen again for other things. People will be raising the alarm about something, and in the media, the nuanced thinking about probabilities will be washed out. You'll hear people saying that X will definitely fuck everything up very soon. And it doesn't. And when the catastrophe doesn't happen, don't over-update. Don't say, "They cried wolf before and nothing happened, thus they are no longer credible." Say "I wonder what probability they or I should put on it? Is that high enough to set up the proper precautions?" When somebody says that nuclear war hasn't happened yet despite all the scares, when somebody reminds you about the AI winter where nothing was happening in it despite all the hype, remember the boy who cried a 5% chance of wolf. Originally posted on my Twitter TL;DR

Applying science to meditation isn’t unique to Jeffery Martin’s course. Fortunately for the world, there’s a whole movement around this. That being said, I haven’t heard of anything that seems more likely to figure out how to actually achieve enlightenment (or fundamental well-being (FWB) as he calls it, which I prefer). Most science I know of is doing things like putting meditators in brain scans and seeing if anything is different from regular brains, or running RCTs to see if meditation makes you happier. This is foundational and important to do. However, it’s very black box thinking and doesn’t give you any gears-level understanding of how to achieve fundamental well-being. Meditation classes usually teach a variety of different techniques. Which techniques are causing the change? Most studies focus on averages, which ignores the thing we’re most interested in - those outliers who don’t just start feeling less stressed but have eliminated suffering. Who are living in states of profound bliss and serenity. How does that show up on a psychological item asking “On a scale of 1 to 10, how satisfied are you with your life?”? The Finder’s Course on the other hand clearly followed a methodology that was truly trying to solve the problem. The way he did this was to find over 1,000 people saying that they had achieved fundamental well-being, and he went and interviewed all of them. The interviews would often last up to twelve hours. He asked them what their experiences were, what had gotten them there, and ran them through batteries of psychological tests. From this exploratory research, he started pulling out patterns. You can read some of the results of his research in his book. He took the top findings out of his research and turned it into a course. It was formerly called the Finder’s Course (a play on the usual spiritual terminology of people being “seekers”). He continues to do science on the course, and this is part of what most intrigued me. It’s mandatory for the course to take a whole battery of psychological evaluations before and after, such as PERMA, satisfaction with life scale, CES-D Questionnaire, etc. After doing a week of each technique, he also does a shorter survey. The results from this he claims are that 65% of people who finish the course achieve fundamental well-being. This is an incredible claim, and I figured it was probably just hype. Then I spoke to a friend he said that he’d recently done the course and could now go into fundamental well-being at will. This is what inspired me to give it a go. Before I started the course, I publicly pre-committed to writing about my experience, regardless of how it went. Usually, people only write about something if it goes particularly well or poorly, and I wanted to help even that out. So, without further ado, here’s my review of the course. What’s in the course and how it works Experiment with different techniques to find your meditation “fit” The main thing that I liked about the course was its underlying strategy:

What Jeffery found was that people who’d achieved fundamental well-being hadn’t just used one technique to get there. Some people got there mostly through concentration practice, others through insight practice, others still through headless way techniques, and so on. He explains his thinking and guides you through a few techniques in this 55-minute video. I’d watch it and if you like it, take the course. This is extremely representative of how the course is. An aside on why if you hate concentration practice, you might enjoy mantra meditation Interestingly, this video might have had as much impact on me as the whole rest of the 6-week course. I’d always struggled with concentration practice, especially on the breath. It had never really done anything for me except cause boredom and frustration. I’d had more or less the same experience with other meditation objects such as listening to the waves or focusing on other parts of the body or a candle. When I tried the mantra meditation he describes in the video, it led to massive breakthroughs in my concentration practice. It went from a mostly boring trial of willpower to one of the most reliable techniques in my happiness workout routine. About 85% of my concentration practice sessions now involve intense joy, with about 40% of the session being spent in joy. This is for a few reasons. You can’t not “hear” the mantra. The breath has always been the bane of my meditation existence. Whenever I tried focusing on it, my breathing would get really shallow and soft, making it really hard to tell what was happening there. I was constantly asking myself “Is this the breath?”. It’s really hard to concentrate on something that’s so subtle. The mantra, on the other hand, is under your control. You can make it as “loud” or as “quiet” as you want. You can slow it down so that you only move on to the next word after you’ve fully paid attention to the current one. You could even say it out loud if you want. I personally find that if I’m starting to get way more distracted, I can just start “shouting” it in my head, and it makes it vastly easier to focus on it. Teachers often say that the breath being subtle is a pro because it forces you to beef up your attention muscles. I think this might be true if you’re already at a certain level of concentration practice, but for me and I suspect many others, it’s too hard too fast. It would be like trying to run a marathon on your first day of taking up jogging after being a couch potato your entire life. You’ve got to build up to it. It’s easier to focus on things that are pleasant Some meditation teachers talk about how calming the breath is. I’m sure that’s true for a lot of people. But for me most of the time it’s pretty darn neutral. Or it gets weird when I’m having interesting meditative experiences, which then takes me out of the experience. The mantra on the other hand is deliberately and consistently pleasant. And that’s just so much easier to pay attention to! It’s so much easier to get yourself to do enjoyable things, and if your mantra is about being grateful for your life, that’s something that will be easier to get your brain on board with. Naturally, this only works for mantras that are pleasant. That’s one of the reasons I recommend against mantras that aren’t in your native tongue and that you didn’t choose yourself. The mantra is your thoughts The main distraction in concentration practice is your thoughts. However, if your meditation object is a mantra, then that is a large part of your thoughts. Your thoughts consist of other things too, like images and urges, but a huge part of many (but not all!) people’s thoughts are verbal commentary. So if your meditation object is the internal narrative, it’s easier to not get distracted and more clearly see when it goes away. I highly recommend trying it out. And just experimenting widely with a bunch of different meditation objects. The general principle of experimenting widely and then drilling down on the ones you find suit you best seems really strong. Some potential meditation objects that aren’t just the breath:

Structure and techniques covered in the course Techniques covered

The techniques are taught via pre-recorded video. Throughout the course, you’re supposed to meditate one hour a day combined with short ~3-minute exercises you do when you first wake up and when you go to bed. There’s no enforcement aside from them asking once a week in a survey which days you meditated. I’d highly recommend doing the course with a friend or partner to help you stick to it. The course was $249 last I checked. It’s a bit pricey for an online course, but the price definitely makes you more motivated to finish it. Results: ambiguous data and imposter syndrome cured So, I took the course. Am I enlightened now? Have I achieved fundamental well-being? Unfortunately, no. Did I improve my happiness? The results are ambiguous. I’ve been tracking my emotional well-being and other metrics for the last seven years, and there doesn’t seem to be any noticeable change before and after the meditation course beyond noise. On the other hand, my emotion tracking is not very sensitive to changes. One of the hardest periods of my life only showed a 0.6 change on a scale of 1 to 10. This was mostly because my coping mechanisms were so good that they masked my misery. On the whole, I’m inclined to not be too concerned about the numbers, because the real headliner of the whole thing is that it probably cured me of my impostor syndrome, reduced my anxiety around work massively, and just made me a much more confident person. How I got rid of impostor syndrome with loving-kindness meditation I was a confident kid, then I worked at 80,000 Hours back in 2013, and living in Oxford gave me impostor syndrome. Turns out that basing your confidence on being a big fish in a small pond only works if you stay in a small pond. Between 2013 and 2022 I had more or less chronic low confidence and high anxiety around work. I tried everything to get rid of it: concentration practice, CBT, IFS, emotional coherence therapy, exposure therapy, ACT, talk therapy, and just plain old reason. Nothing made a dent. Then the first week of the Finder’s Course was doing an hour a day of loving-kindness meditation. I’ve done a bunch of loving-kindness meditation in the past, but it was always more of a “dessert” technique. After I’d had my vegetables of concentration practice, I could treat myself with 2-5 minutes of loving-kindness at the end. It was never the main course. This first week though was one hour a day on just loving-kindness. It was amazing and profoundly changing. There are a lot of different loving-kindness techniques. The one that I was doing was the one where you:

At first, I focused on feeling loving-kindness toward others. That’s always been pretty easy for me. It was lots of fun, just radiating love towards people in my life and the world. Then, inspired by this amazing post by Charlie Rogers-Smith on self-love, I tried turning it on myself. What if I tried radiating loving-kindness towards myself instead of others? Immediately, a wall slammed down in my mind. “No,” a part of me said. “You definitely cannot love yourself.” I immediately burst into tears. So, you know, a perfectly healthy reaction. While this session wasn’t exactly the most enjoyable one I’ve ever had, it was possibly the most fruitful. After a brief temptation to avoid such negative feelings, I realized that this was the clearest signal I was ever going to get to dig deeper. I decided to dedicate the week to loving myself in particular. I started with an easy source of loving-kindness, then tried to find things about myself that were easier. At first, everything was hard. Could I love myself when I was doing good things? No. OK, how about bad things? Heck no! Maybe I could imagine liking myself when I was a kid? Still a no. OK, what about as a baby? Surely there can’t be any reason to not love myself as a baby! Nope. I was a pudgy baby. And clearly you can’t love pudgy babies. Eventually, I found my “in”. I could imagine being my mom, holding my baby-self, and feeling how she felt about me. Even if I had a lot of self-dislike, I am extremely confident my mom loved my baby-self. From there, I was able to build up. I realized it was easier to love myself when I imagined previous times in my life when I was suffering. From there I felt love for myself in particularly potent scenes from my childhood. After a while, it was easy. I then started applying the same strategy, but towards feeling confident directly. So establish the feeling of confidence by imaging a scene that brings it up easily, then start working towards harder and harder scenarios. There’s more to it than that, but this is already becoming a rather long post. I think it would be useful to have a fully written up explanation of my techniques for anxiety/confidence, so I’ll write that up in a separate essay. If you want to hear about it when it comes out, just follow me on Twitter, my personal blog, or set the forum to notify you when I post next. Overall though, it’s been about six months since the shift, and it’s felt remarkably stable. There have been a couple of times where I’ve reverted to beating myself up again, but it’s lasted max a couple of hours. This is especially amazing because I haven’t done the meditation regularly for five months now, and I’ve never had a stretch of confidence this long in the last ten years. Of note though, while I was practicing regularly my confidence was about a 9/10, and since not practicing regularly it’s stabilized at around a 6.5/10. This is still amazing though compared to my 3/10 confidence previously. And a friend of mine went through the course with me and she hated the loving-kindness meditation week. So I already know this won’t work for everybody. However, this has affected the quality of my life and my work so much that I think most people should give it a shot. I feel way more resilient. I feel far less anxiety. I feel more motivated to work on AI alignment. I’m far better at receiving feedback because it doesn’t threaten my self-worth. I feel more secure with my friends. I enjoy my work more because I’m not constantly beating myself up. Try one hour a day for a week and see how you feel. Things I liked and disliked about the course Spiritual blue balls The loving-kindness meditation week was one of the happiest of my life. But then it was the next week and it was a meditation that was most definitely not a fit. It followed this pattern, where I’d be super excited about a new technique, then I’d have to put it on hold until the end of the course. By the end of the course, I was so glad it was done so I could just focus on the ones that were working for me. Of course, I don’t think this is a flaw really. This is to be expected if only some techniques fit you. This would have mostly been fine if it hadn’t been for- The weird obsession with the nose Following the first week was around three weeks of concentration and noting practice that nearly destroyed me. It was your typical concentrate on the breath practice, but they firmly insisted you could only pay attention to the nose. Most teachers usually let you choose between the chest and nose, wherever you feel it the most clearly. But not this class. In this class, it was nose or bust. The problem was - I couldn’t feel my nostrils at all. In the lecture, he said that everybody had sensations in their nostrils unless there was something really wrong with them. I mean, if you shoved a chili pepper up your nose, surely you’d feel it? Sure, I’d feel that. But that’s a far cry from sitting still and having my breath get softer every minute. I asked if I could focus on my chest since that was so much clearer to me and they said no. That I should just keep focusing on the nose area and usually feelings will start coming up, and if there wasn’t anything, just to focus on there being nothing. Focus on nothing. . . This worked so poorly that it has become a joke in my house about me ranting about the Nostril Weeks. It lasted about three weeks, and I did an hour a day, even when I got covid part way through. Funnily enough, covid actually made it better because then I could feel my nostrils because my nasal passages were so blocked. It was torture. Eventually, I could feel the slightest of sensations on the out-breath, but it was so subtle it could have just been my imagination. In the end, I periodically added a mint-scented medicine to my nose so I could feel something there, but then it was mostly slight pain, which is a difficult meditation object. Why did they insist on the nostril? I don’t know for sure and they didn’t answer when I asked why, but I have a few hypotheses for their reasoning. One is that they wanted you to focus on a really narrow patch of sensations. This would help you achieve more genuine single-pointedness. The other is that they were giving pre-recorded video lectures, and it added complexity to the instructions to allow for multiple meditation objects. Finally, maybe there’s something special about the nostril that leads to more enlightenment that’s hard to put into words. In the end, that was just a really difficult three weeks, and I wouldn’t recommend it. I think if I had just switched to doing concentration and noting practice on a mantra or my chest, that would have been way better. If you have the same issues, I’d just give the nostrils a couple of days, to see if maybe you can sensitize the area, and if not, switch to a meditation object that’s a better fit for you. His epistemology wasn’t the worst, but also wasn’t the best If you are allergic to non-rigorous epistemology, I would stick to:

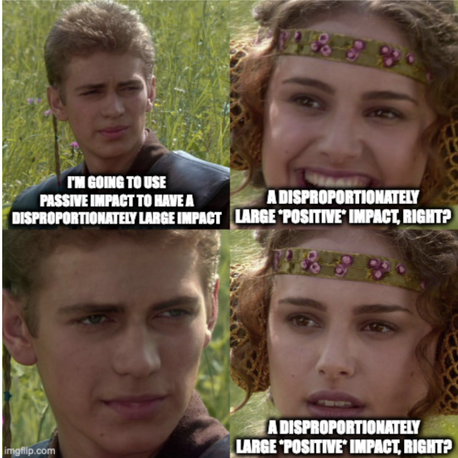

However, I think you’ll be seriously missing out on a lot of really important psychological wisdom if you can’t learn from people who have sub-optimal epistemologies. Just because somebody believes a lot of things that are wrong doesn’t mean that everything they believe is wrong. To be fair, I don’t think his epistemology is bad for a meditation teacher. In fact, it’s far above average. However, he definitely made some very bad arguments in a substantial fraction of his videos, and his surveys imply that he believes in meditating leads to good things happening to you (i.e. law of attraction). Just wanted to flag it for the people who are more sensitive to that sort of thing. Publicly promising to write about it as a commitment and learning device This isn’t part of the course, but it’s something I wanted to share because it worked so well for me. Before I started the course, I committed to writing about my experiences, and this definitely made the course better for me. Knowing that I’d said it publicly made me stick with it, even when it was really hard. It also made me learn better because I knew that I would have to explain it to people afterward. I highly recommend it. The polish of the course could be improved a lot Right now a huge drawback to the course is that it looks a little scammy and unprofessional. I think if they invested in improving their website that would go a long way toward improving their offering. The importance of hour-long sessions I’ve always been averse to doing longer meditation sessions. Giving up even half an hour of my day feels like such a sacrifice. When Jeffery said that it was imperative to do an uninterrupted hour a day, I really didn’t want to believe him. And yet, I put at least a 20% chance that I would not have fixed my impostor syndrome if I hadn’t done hour-long sessions. My initial insight into my lack of self-love was 45 minutes into a session. I think part of the reason I was able to avoid noticing this side of myself for so long was that I just looked away if I got too close to it. I have also noticed that I haven’t hit diminishing returns for meditating yet. I’ve regularly practiced anywhere between 10 minutes and 2 hours per day, and with 10 minutes a day, I barely notice a difference, whereas when I do 2 hours regularly, it feels as if I’m floating on a cloud of joy all day. Of course, 2 hours is a lot and I’m not sure it’s worth the trade-off compared to counterfactual uses of time. However, I think it’s correct to model meditation like exercise: doing even a small amount can help, but it’s hard for most people to do it too much. Different meditation techniques do indeed work differently for different people My favorite week by far was the loving-kindness week. For my friend, it was the worst. I mostly felt nothing for the body scan week, and my friend practically got drunk on it, feeling super giggly after each round. It might seem obvious in retrospect, but I feel like this is a really important thing to both acknowledge and work with. This is by far my favorite part of the course. If you do the body scan and aren’t feeling anything after a week, just move on. Life is too short to waste on techniques that aren’t doing anything for you. The Buddha is famous for saying to not take his word for anything but to try it for yourself and see if it works. People say that, but then don’t walk the walk. Jeffery Martin does, and I love that about the course. Do I recommend it? Overall, yes. I don’t know of any courses that have as good a chance of leading to substantial increases in your well-being. If you’re excellent at self-directed learning, I think you can get most of the benefits outside of the course, or maybe make it even better. Simply commit to doing each of the techniques for an hour a day for a week. I’d consider adding other techniques too, such as internal family systems, cognitive behavioral therapy, journaling, and other techniques you’ve tried in the past with some success or you think might work well for you. If you don’t have the commitment device of paying a large sum of money for it, I’d add some alternatives. Making a public commitment on social media and/or doing it with a friend or two would probably do it. Better yet, pre-commit to writing your own review of it. I’d be really interested in hearing about other EAs’ and rationalists’ experiences with the course, and it’s an amazing commitment device. by Kat Woods, Amber Dawn What’s better - starting an effective charity yourself, or inspiring a friend to leave a low-impact job to start a similarly effective charity? Most EAs would say that the second is better: the charity gets founded, and you’re still free to do other things. Persuading others to do impactful work is an example of what I call passive impact. In this post, I explain what passive impact is, and why the greatest difference you make may not be through your day-to-day work, but through setting up passively-impactful projects that continue to positively affect the world even when you’ve moved on to other things. What is passive impact? When we talk about making money, we can talk about active income and passive income. Active income is money that is linked to work (for example, a salary). Passive income is money that is decoupled from work, money that a person earns with minimal effort. Landlords, for example, earn passive income from their properties: rent comes in monthly and the landlord doesn’t have to do much, beyond occasional maintenance. Similarly, when we talk about our positive impact, we can talk about active impact and passive impact. When most people think about their impact, they think about what they do. A student might send $100 to the world’s poorest people, who might use this money to buy a roof for their house or education for their kids. Or an AI researcher might spend 2 hours working on a problem in machine learning, to help us make superintelligent AI more likely to share our values. These people are having an active impact - making the world better through their actions. Their impact is active because, in order to have the same impact again, they’d have to repeat the action - make another donation, or spend more time working on the problem. Now consider the career advisors at 80,000 Hours. Imagine that, thanks to their advice, a young person decides to work for an effective animal advocacy charity rather than at her local cat shelter, and thus save hundreds of thousands of chickens from suffering on factory farms. The 80,000 Hours advisors can claim some of the credit for this impact - after all, without their advice, their advisee would have had a much less impactful career. But after the initial advising session, the coaches don’t need to keep meeting with their advisee - the advisee generates impact on her own. This is what I mean by passive impact: taking individual actions or setting up projects that keep on making the world better, without much further effort. The ultra-wealthy make most of their money through passive income. Bill Gates hasn’t worked at Microsoft since 2008, but it continues to make money for him. Similarly, many highly successful altruists are most impactful not through their day-to-day work, but through old projects that continue to generate positive impact, without further input. Why should you try to create passive impact What are the benefits of passive impact? Here are a few: You can have a really big impact Your active impact is limited by your time, energy, and money, but your passive impact is boundless because you can just keep on setting up impactful projects that run in parallel to each other. It’s satisfying It’s really pleasing to be lounging on a beach somewhere and to hear that one of my projects has had a positive impact. It’s more efficient When I set up the Nonlinear Library, people asked me why I didn’t get a human to read the posts, rather than a machine. But by automating the process, I’m saving loads of money and time. It will take a robot two weeks and $6,000 to record the entire Less Wrong backlog; if we’d hired a human to read all those posts, it would take many years and over a million dollars. It’s more sustainable Since active impact takes time, effort, and money, projects that involve ongoing input from their founders are more likely to fizzle out. Passively impactful projects can just keep going, as machines or other people take on the effort. It’s more fun Many entrepreneurs thrive on variety and excitement and are easily distracted. If you found passively-impactful projects, you can move on to other projects as soon as you’re bored, and the original projects will continue to have an impact. As Tim Ferriss has said: interests wane; design accordingly. Pitfalls and caveats Passive impact is a powerful tool and like most powerful tools, it’s a double-edged sword. Here are some things to watch out for when trying to have passive impact. Take care not to create negative passive impact Of course, impact can be good or bad. If you set up a passive impact stream, but then you discover that it is having a negative impact, then that’s really bad, because it might be harder to stop. For example, imagine that I persuade a friend to work for a certain charity, but I later discover that the charity is causing harm. Unless I can persuade my friend that the charity is bad, I’ve created passive negative impact.

Passively impactful projects can fizzle out Passive impact streams can decay and disappear - nothing is 100% passive. Landlords need to arrange for routine maintenance, and passively-impactful people still need to put some effort into their passive impact streams, through management (for projects run by other people), debugging (for automated projects), or other things. Passively impactful projects can go in unexpected directions If you delegate a project to other people, they might take it in a very different direction from what you originally intended. You can make this less likely by delegating the project to people whose values are very similar to your own. How to have passive impact Automate You can have passive impact by using machines to do things automatically. For example, I set up the Nonlinear Library, which automatically records new EA-related posts. This increases the impact of those posts (since some people might listen to them who would not otherwise have read them) but requires little ongoing maintenance. Delegate You can have passive impact by setting up an organization then having other people take over. For example, Charity Entrepreneurship teaches people how to found effective, impactful charities. Since the charities it incubates exist (in part) because of them, some of the credit for the impact of those charities goes to them, even though they’re only involved at the beginning. (We’re now running a similar incubation program at Nonlinear, incubating longtermist nonprofits). Another way to delegate is to decentralize. This way, projects can take on a life of their own, without your active management. Ideas You can have passive impact by coming up with - and writing down - useful ideas. For example, Ben Todd’s idea of counterfactual considerations has helped a lot of people to think more clearly about their career plans, but he doesn’t have to personally keep explaining it to people - he can simply send them a post about it, or others can explain it. Capital Just as you can generate passive income by using capital that you already have (by buying stocks, or a house, or a business), you can also have passive impact that way. For example, at Nonlinear we set up EA Houses, a project that matches up EAs with spaces where they can live. If you have a spare room (for example), you can volunteer to host an EA. You can have passive impact yourself by housing EAs who are having an active impact through their career. As an EA, you might have already spent lots of time thinking about your active impact: how to do the most good with your career or your donations. This is great, but I think that more EAs should consider their passive impact as well. Will you have the greatest impact through your day-to-day actions? Or can you spend a limited amount of time, effort, and money to create a passively impactful project that will keep on making a difference, changing the world before you even get out of bed? This post was written collaboratively by Kat Woods and Amber Dawn Ace as part of Nonlinear’s experimental Writing Internship program. The ideas are Kat’s; Kat explained them to Amber, and Amber wrote them up. We would like to offer this service to other EAs who want to share their as-yet unwritten ideas or expertise. If you would be interested in working with Amber to write up your ideas, fill out this form. My first (1) experience with academic ethics convinced me to stop trying to be ethical.

I was 18 years old and trying to figure out what to do with my life, so I had the silly thought, “Oh, that’s what ethics is about! Ethics is about figuring out what one ought to do.” I promptly went to the university library and got out an intro to ethics book called “Ethics” and read it cover to cover. Each chapter had the same structure: 1) Introduce a possible moral theory and reasons to believe it 2) Introduce all the devastating counterarguments against that view I kept reading, dying with curiosity to find out what the answer was in the last chapter. The Last Chapter where they told me which moral theory didn’t have anything critically wrong with it. … You can predict how this is going to turn out. I remember reaching the end of the last chapter and saying to myself, “Well, I can’t even be a nihilist, because I know all the problems with that theory too!” I decided then not to really bother trying to figure out ethics or how to do good things or what was right. It was only a year later that I saw a documentary about some horrible thing happening in the world that jolted me into realizing that this was too important of an issue to just relegate to a shoulder shrug. The suffering in the world is too great to just say, “Who knows what we should do?”. The Moral of the Story Not sure what the moral of this story is. Maybe it's that ethical philosophy is confusing and confused? Maybe it's that you should skip to the last chapter if you think that's where the answer is? Maybe it's that you need to pair the intellectual effort of figuring out what is "good" with the real life reason why it's important? Maybe it's that figuring out what is ethical is an unsolved problem, an open question that you should continue trying to answer throughout your entire life? Who knows? Although, I do feel that this story ending with an ambiguous message seems apt, so let's leave it at that. (1) My actual first experience with academic ethics was when I was 16 and I stumbled across a book of Plato's writings. The first chapter explained how the only true love was between a man and a boy. But let's just move right along. If you want to start a charity, you need to be learning constantly. You’ll inevitably learn by doing, but it will save you a lot of heartache to also learn from others.

If you’re interested in potentially starting a charity or are already running one and want to continue improving your org, here’s what we at Nonlinear think will be useful to read. We don’t recommend reading these in order or start to finish. Skim them ruthlessly, jump around to the ones that seem relevant to you, and try to really engage with the ones that are genuinely useful to you.

Most people reading this will reasonably not read all of the above. In that case, consider reading summaries. For example, Blinkist and Shortform have summarised lots of nonfiction books, and audio format is available for most of them. Shortform is also nice because it makes it a lot easier to actually do the exercises in the books, which is where a massive amount of the value is. Of course, the last thing we’d want is for you to procrastinate on founding a charity until you’ve finished this list. You should always have two parallel “departments” running in your life: learning and doing. Always be building. Always be learning. Finally, if you’re here, that’s probably a pretty good sign that you should consider applying to be incubated by Nonlinear or Charity Entrepreneurship:

If your dream job is to work in longtermism, be your own boss, and talk to EAs all day, then you might be the perfect fit for starting an EA recruitment agency through Nonlinear’s incubation program.

To find out more about the idea itself and why it’s high impact, read below. For more details about how to tell if you’re a good fit, what support we provide, and how to apply, see the second half of the article. If you think this is an important charity to have in the EA space, please like and share this Request for Founders so that the right people see it. Deadline: February 1st, 11:59pm EST Fill out this form to apply Why it’s high impact to start an EA headhunting agency The idea is for you to start an organization that helps hire employees for longtermist orgs. This will help the world in a few ways:

What roles will the startup hire for? Nonlinear’s research team has identified hiring PAs as one of the best use cases of a hiring agency in EA. This is for a few reasons. Firstly, as 80,000 Hours describes in their career guide, PAs can be a high-impact role. Ben Todd says it better than me here: “Consider: if you can save that researcher one hour spent on activities besides research, then that researcher can spend one more hour researching. So, by saving that researcher time, you can convert your time into their time. Suddenly, one of your hours becomes one more hour spent by the best researcher, working in the best field!” Put another way, imagine you could add another Paul Christiano, Eliezer Yudkowsky, or Chris Olah to the alignment community. With a PA hiring agency, you could essentially do that by getting the top researchers PAs. To use an extremely oversimplified example, say a PA increases the output of a researcher by 10% on average. That means if you hire ten PAs for the top ten researchers, that’s the equivalent of adding a top AI safety researcher. It’s hard to put a dollar estimate on the value this would add to the world, but if you’re convinced of AI safety, it’s extremely high. Secondly, PAs are particularly well-suited to a hiring agency. This is because of two main reasons:

Once you’ve created optimal systems for hiring PAs, the org will expand to helping EA orgs hire for other roles. How you proceed will depend on what strategy you think is best. Some potential roles that could benefit from a recruiter include:

What about BERI, CampusPA, 80,000 Hours, and non-EA recruitment agencies? BERI already hires PAs for longtermists, but only for a few academic research institutions. Their strategy for the foreseeable future is to stick to these orgs, specializing in helping longtermist academic institutions, so they won’t be filling the gap. CampusPA hires PAs for EAs. However, they only hire remote PAs, which is a dealbreaker for many. They also focus specifically on PAs and are unlikely to switch to hiring for other EA roles. We spoke to them about switching and it doesn’t fit with their business strategy. 80,000 Hours used to do recruiting, but they stopped because their strategy is to do a few things extremely well instead of spreading themselves too thin. We spoke with Niel Bowerman and he’s really excited for somebody else to take the baton since he thinks it would be high impact. What about just using non-EA recruitment agencies? Generally, we shouldn’t make an EA-specific organization when a non-EA one will work just as well. In the case of a non-EA hiring agency, the reason we think that an EA will have a comparative advantage is that to hire for EA orgs, you need to have an EA network and know how to get EAs excited about certain jobs. This is true for most roles you’d be hiring for. Even PAs, who don’t need to be EAs, often will be simply because they will be more aligned with the general mission of the person they’ll be assisting, leading to more talented people from the EA community applying than from those outside of it. Finally, even if there was another org working on this, we think there's room for at least three full-time people working on this, potentially even more. If we get enough good applicants, we'll likely just incubate multiple people. Why you might want to start this charity

You’re a good fit for starting this charity if:

What the incubation program provides Nonlinear’s incubation program provides two main benefits: seed funding and mentorship. Seed funding The seed funding will be for up to a year’s salary, although you’ll also have the option of using that money for other things, such as hiring other people. This way you can have some runway to establish yourself before you have to start fundraising or charging commission. Mentorship You will receive bespoke training and guidance from two experienced entrepreneurs, Nonlinear founders Kat Woods and Emerson Spartz. Kat Woods previously founded Charity Entrepreneurship and Charity Science Health (now Suvita). Emerson Spartz is a Forbes 30 Under 30 who founded the #1 Harry Potter website when he was 12 and then built websites with a monthly audience rivaling the New York Times. The training will be catered to your particular background. If you have a lot of experience with management and little with marketing, you’ll get training in marketing. If vice versa, then you’ll get training in management. You’ll start with more intensive, daily guidance, then you’ll graduate to less and less frequent check-ins until the training wheels are completely taken off. After that, you’ll be on your own, though there will always be the option to request that Kat and/or Emerson be board members of your charity. The length of the incubation period will depend on your current level of expertise. If you’re already an experienced recruiter, then the incubation period could be as little as one month. If you’re relatively inexperienced, it could be as long as six months. The incubation can be done remotely from anywhere in the world. Should you apply? We accept candidates from a wide range of backgrounds. You can be a recent high school graduate or have a decade’s experience recruiting. Experience is helpful but not necessary. We’ll help you develop the skills you’re currently missing. What matters most is grit, altruism, and intelligence. If you’re uncertain, you should err on the side of applying. Impostor syndrome is rampant in EA. In fact, around 50% of Charity Entrepreneurship’s most successful founders from previous years didn’t even think they should apply. Application process To apply, fill out the form here. If you already have your CV ready, it should take around 30-120 minutes to fill out. Deadline: February 1st, 11:59pm EST If you think that having an EA hiring agency is a high-impact idea, please share this request for founders on social media or upvote it to make it more likely that the right person sees it. This is part of a series where I write about my stay in Rwanda and Uganda and what I learned that might be helpful from an EA perspective.

You can see the full list of articles here, which I will add to as they come out. One of the questions I asked people throughout Rwanda was, “If a charity came to your village and they could send either ten children to primary school or one person to university, what would you want them to do?”. Depending on their answer, I would change the ratio. For example, if they said that they’d choose to send the person to university, I’d ask them, “What if it was one hundred children to primary school? What about one thousand?” By and large, most people would far prefer to send one person to university compared to tens to hundreds of people to primary school. Of the people I spoke to, 85% said that they would prefer to send one person to university over one hundred to primary school. More than half kept the same answer when it was one thousand to primary school. When I asked why, the answers were almost always that primary school was not useful. They didn’t just mean that it wasn’t a good quality education. They also thought that the person would just continue to farm with a primary education. No change in their outcomes. Meanwhile, if somebody goes to university, they can not only get out of farming and make real money, but also come back to the village and pass along anything they’ve learned. Those who said they’d prefer primary said that it was because they didn’t want to leave people out, and they couldn’t prioritize one person over ten. Of course, I must add the usual qualifiers that this was a small sample size (twenty people), there are many ways that if you changed the wording you’d get different answers, and so forth. You can read more about what I learned about methodology limitations here. If you liked this post you might also like: |

Popular postsThe Parable of the Boy Who Cried 5% Chance of Wolf

The most important lesson I learned after ten years in EA Why fun writing can save lives Full List Kat WoodsI'm an effective altruist who co-founded Nonlinear, Charity Entrepreneurship, and Charity Science Health Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed